* This paper is a Master’s thesis for the Department of Sociology at Seoul National University.

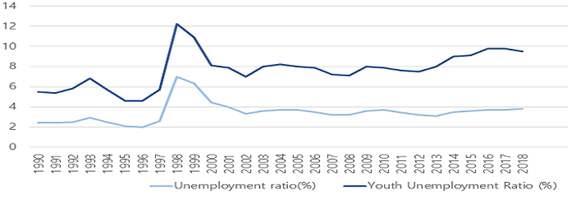

This study analyzes the process of social politics regarding the social question of unemployment, focusing on institutional change of the Seoul City Youth Allowance (YA). Since the financial crisis in South Korea in 1997, unemployment has been a chronic social problem in the form of youth unemployment, which has maintained an alarmingly high rate compared to other generational groups.

YA, a policy of sending monthly cash transfers amounting to KRW 500,000 to unemployed young adults for up to six months, was proposed in the context of a variety of other prior institutions and discourses established to address the problem of youth unemployment which had been expected, but ultimately failed, to contribute in a positive manner to increased production.

The YA policy, accused of imprudently distributing “fish” to an undeserving young generation, has been under intense political scrutiny, due to its appearance which stands in radical contrast to conventional policy approaches of providing youth with jobs by which they “could catch fish for themselves.”

This study focuses on the discursive disputes between different political stances which regard the money from the YA in various ways, such as “gifts,” “investments,” “rights,” or “shares.”

|

YA as “giving” |

Youth |

Recipient |

How to represent the visage of the youth? |

|

Allowance |

Gift |

Why should this money be allocated to youth? |

As implicated in its title, “Youth Allowance,” the political contestation surrounding the YA constitutes a strategic viewpoint from which to observe the (re)construction of the norms that define what kind of giving to the youth is acceptable. In this regard, this study investigates how money can be acceptably granted to the youth, who have been hitherto understood as being part of the working age population. This question can be further divided into the following questions:

First, how did youth come to be discussed as an object of social policies which grant cash to members of the working age population? (Chap 2)

Second, how does the policy recognize the “youth” and thereby how does it construct the meaning of money given to the youth? (Chap 3)

Finally, through the process in which the original idea materialized into policy, how has the norm of giving to the youth been transformed? (Chap 4)

In order to situate the YA policy in its historical context, Chapter 2 examines how the generational category of the youth became an object of social policy which provides grants to the working age population. The youth, nestled between the categories of the child, an object of nurture, and the adult, the subject of labor, initially emerged as a category for government policy to with an effort to tackle unemployment after the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

Youth unemployment, first understood as a matter of individual moral responsibility, was later constructed as a problem to be addressed at the collective level, due to social concern for the “youth generation.” Afterwards, the social politics of youth unemployment started to mingle with the cultural politics over the discursive construction of the youth generation. The stakes of this political struggle pertain to what representation, recognition, and redistribution the youth deserve.

|

|

Government’s Youth Policies |

Youth-led Social Movements |

|

Norms of the youth |

Restoration |

Reconstruction |

|

Policy |

Support for job-seeking and job-creating e.g. social venture, startup, |

Collective claim to the social rights: working conditions for irregular laborers, reduction of tuition fees, adequate housing supply, lower debt |

|

Representation |

Listening to the youth |

Self-representation |

|

Recognition |

Passion, Striving, Innovation Social group that can overcome their own crisis |

Social group that epitomizes the crisis of social reproduction |

|

Redistribution |

Workfare “A job is the best welfare” |

Right to social reproduction |

|

Temporality of Youth |

Prospective future |

Never-realizing such future, Semi-permanent dismal present |

The government has focused on policies that support job-seeking and job-creation. Under the premise of youth unemployment being a temporary crisis that can be quickly overcome in the near future, thereby restoring the norms of youthfulness such as striving, passion, and opportunity. On the other hand, however, a number of youth have organized social movements that demand recognition of their collective right to social reproduction, claiming that the premise of conventional policy approaches that promise future employment is outdated. As the movement of the youth representing themselves has begun participating in policy governance in Seoul, led by a former civil activist, the structure for political opportunity which yielded youth policy, such as the YA, has been institutionalized.

The YA, which is officially titled the “Youth Activity Support Program,” was conceived through a process of reconstruction of the meaning of “youth” and then providing an allowance to the youth. In Chapter 3, the meaning of “youth” (construction of the problem), “activity” (point of policy intervention), and “support” (the content of the policy), the concepts which constitute the original policy design, are analyzed in order.

The policy approach which addressed the youth as only transitional job seekers was heavily criticized. This critique led to the construction of a novel policy category, the Youth outside society, as opposed to NEET (Not in Employment, Education, or Training), and it includes youth who are marginalized due to structural problems of the labor market. The temporality of youth was thereby transformed from being a transitionary period of preparing for future employment into the semi-permanent period of job-seeking—which even extends beyond finding a job—during which problems are generated.

As the temporality of youth changed, the purpose of youth policy was readjusted to focus on the task of preserving the multiple human capacity referred to as “active energy” (Hwal-ryeok [活力]), instead of accumulating skills for the enhancement of employability. To fulfill this goal, autonomous “activities” planned by individuals instead of economically necessitated job-seeking and precarious labor situations were suggested as an alternative policy direction.

Third, the YA was proposed as a support fund for the aforementioned activities. Policymakers employed the logic of providing unconditional “gifts” and conditional “investments” in order to construct the meaning of this money as a “right.” This money was regarded not only as unconditional gift that guarantees maximum autonomy for the individual recipients but also as a conditional investment that demands the individual change in the future as a “return” on the investment. However, the significance of this ambiguous investment has yet to be materialized: both the payback period of the investment, which is approximately equivalent to the ill-defined time of youth, and the conditions of the investment. The “activity,” for which the product is to be assessed by the investee, was not clearly defined in the established policy language.

|

|

Employment Success Package (Conventional Government Policy) |

Seoul Youth Allowance |

|

Temporality of Youth |

Future |

Semi-permanent present |

|

Construction of Youth as Policy Category |

NEET |

Youth Outside Society |

|

Policy Goal |

Enhancement of human capital |

Preservation of human capabilities (“Hwal-Ryeok”) |

|

What the Policy Supports |

Job-seeking |

Activity |

The YA was transformed through intense political controversy immediately after it went public outside the Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) in November 2015. The administration and the ruling party, who claimed they had the legal authority to block the policy, could not understand the novel policy category of “activity,” which underpinned the core of the policy, and therefore labeled the policy an unconditional cash transfer. Consequently, the YA was criticized as an immoral charity to undeserving youth who were deemed to be part of the working age population.

In response, since January 2016, the SMG opened consultations on the policy with the dissenters and revised the definition of the “activity,” to be job-seeking activities in a broad sense. Accordingly, the meaning of the YA was changed into an effective investment in the youth as human resources, who are being envisioned as the future work force. Despite the SMG’s attempt to coordinate with the administration based on the norms of the youth and giving, the consultation eventually broke down, at the end of June 2016, due to irreconcilable discrepancies between the SMG and the government regarding the scope of supported “activities.”

As a result, starting July 2016, instead of the controversial policy category of “activity,” the fact that this program grants cash to the youth was raised as the key issue of the debate. Nevertheless, the meaning of the cash here was not the right to the unconditional distribution which had been hitherto a taboo according to traditional norms. In this context, the youth was represented as prospective job-seekers who are equipped with the ability to lead the future, credibility, and deservingness to be invested in. As a result, the meaning of the YA was adjusted to being a support fund for job-seeking on the institutional level, and the rights implicated in the money granted became the “right to be invested in” for the future.

|

|

Employment Success Package (Conventional Government Policy) |

Seoul Youth Allowance |

|

Temporality of Youth |

Future |

Semi-permanent present |

|

Construction of Youth as Policy Category |

NEET |

Youth Outside Society |

|

Policy Goal |

Enhancement of human capital |

Preservation of human capabilities (“Hwal-Ryeok”) |

|

What the Policy Supports |

Job-seeking |

Activity |

In conclusion, the social politics over the YA established certain precedents which have enabled the direct transfer of money to the youth who had been previously understood as no more than the subject of production. This study understands this new norm as “the right to be invested in.” The norm reflects both the possibilities and limitations of the logic that the working age population can be granted cash. This norm may displace the crisis of unemployment that has been experienced by the youth with an emphasis on individual efforts of prospective investees. On the other hand, this norm constitutes a political ground based on which the social right could be reconstructed, when the period of “youth,” that corresponds to the time of being invested in, is gradually prolonged along with the ongoing recession.

댓글